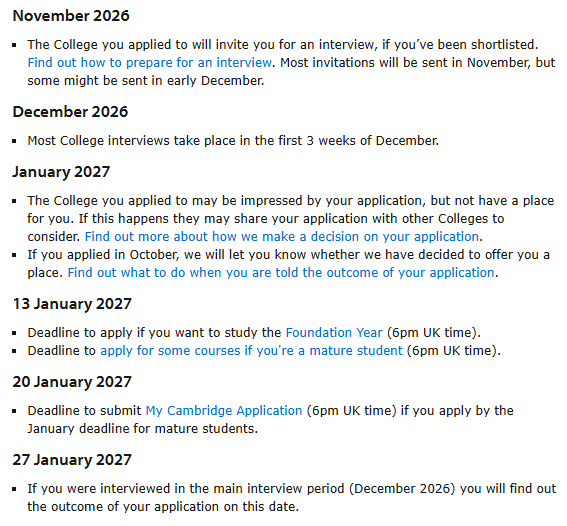

2025 WSDA全国总决赛PF辩题投票吸引了上百名WSDAer的参与经过WSDA会员的投票,现在重磅揭晓三个候选辩题的票选结果:

“Education”领域的公共论坛式辩论辩题以占据总票数近50%的绝对领先地位当选!

中学组-公共论坛式辩论

Public Forum Debate

Resolved: Funding for humanities in higher education should be substantially decreased.

高等教育中对人文学科的资助应大幅削减。

同时,经过WSDA组委会的充分研讨与评估,Junior即兴辩论的前两轮备稿辩题也正式公布!

小学组-即兴辩论 Round 1

Junior Debate

Pets should only be adopted instead of purchased.

宠物应该被领养,而不是购买。

小学组-即兴辩论 Round 2

Junior Debate

Using robots to replace humans for jobs is more beneficial than harmful.

使用机器人取代人类工作利大于弊。

这道高票当选的PF辩题,为何能激起如此广泛的讨论与共鸣?它承载了哪些深刻的现实关切?

又为赛场思辨打开了哪些切入口?相信这份辩题背景解析

一定会对备赛的你有所启发!

Words from the proposer

01

A few clarifications of details

“Humanities” as a unified identity for a number of disciplines is certainly too simplistic for a lot of practitioners ,and will likely prove increasingly so in the future; and more than occasionally the line between humanities and social science could be quite blurry. It should be noted that in the Chinese language, a more familiar categorization is the (more coarse) binary “文科”(arts/literary subjects) and “理工科”(science/engineering subjects), where the division between humanities and social science is much less clearly made. I certainly don’t want the debaters to be distracted on side details of whether a certain subject does or does not belong to “humanities,” though I do acknowledge that such definitional ambiguities could sometimes yield to meaningful discussions—for example, on how humanities should become more scientifically rigorous (e.g., development of quantification methodology or digital humanities) or on how sciences need to leave enough professionalized space for humanistic and critical interpretation (e.g., development in history/philosophy of science). I do wonder if it would be better to include “social science” to the resolution, though I sense that this much ambiguity could be quite dangerous.

I could be overthinking or simply wrong with this, but I do worry about one potential break of balance in this debate, which is on language studies: I think it almost indisputable that the development of AI would massively decrease the need of translators and thus language studies. I could somehow conceive a debate where pro concedes to con on the entire spirit of debate (on the importance of cultural reproduction) and give up all other humanities subject but wins one argument that “we no longer need such big language departments” (surely there are a lot of language departments, and in China, language studies might remain the very few indisputably humanities disciplines) and tips the debate too conveniently.

I hesitate a bit with the resolution wording: should I make this an explicit policy debate, as the current wording suggests, or potentially an evaluative debate with wording such as “decrease of funding in humanities is more beneficial than harmful.” Which is more appropriate depends on whether we are to take humanities funding cut as an ongoing process or a given fact or done deal. I personally lean toward the former as I think this trend has not stopped (and might be irreversible within the foreseeable future), and it might still be sensible to place debaters in the shoes of the policymaker.

02

Popularity

Overall, the proportion of humanities & social science students is considerably higher among the debater and coach demographic. For this reason, I believe this topic might be more relevant to a lot of debaters on a personal level, especially as a good part of them might be thinking about college majors. It would also resonate well with coaches, especially those who once were or still are students in humanities or social science, as the existential question “what’s the value/use of what I study” hardly evades the notice of any conscientious humanities student. For a lot of coaches, teaching this topic (certainly true for this proponent) might serve an additional purpose of personal career reflection, adding to it a mysterious lustre of self-referentiality. For non-humanities students, the topic would be no less relevant, as they would almost certainly at some point confront the reality of the market for certain knowledge and skills. The tension between the liberal view that takes education as intrinsically emancipatory and the pragmatic/materialist view that takes education as socially instrumental would be of increasing importance in an age where access to knowledge has been radically democratized by the massive proliferation of information and where the social hierarchy of distribution of cultural capital and the symbolic power of formal educational attainment are facing unprecedented crises.

03

Accessibility

This resolution is a very novice-friendly topic in its low barrier to research entry and affinity to student experience. The “usefulness of humanities” is one of the most hotly debated topics on an extremely wide range of social platforms, especially in China. For those students who are either unfamiliar with the research process or face larger language barriers with research in English, it is relatively easy for them to self-educate into considerable depths of the resolution. What I particularly appreciate in this topic is its nearly anti-technocratic nature: one does not need to be an expert or become highly specialized in some niche area to make a valuable contribution to the discussion. It would be beneficial if debaters could better understand the evidence they use (far too often with other niche areas about which a normal high school student is scarcely expected to know anything, debaters spit out cards that they don’t understand and become fake experts, only knowing the existence and names of technical terms with fairly little personal understanding of the evidence). In addition, for debaters who have been involved in the AI in education topic, hopefully some of their previous research about the future of education could prove helpful.

04

Ground

Given there are so many discussions about the precarious state of humanities in recent years, that there is ample ground for this debate is almost self-evident. It is a topic for which it’s easy to find facts, one of the most illustrious among which is Harvard University's recent cancellation of over 30 classes (mostly in humanities) in fall 2024. “Crisis of the humanities” has become such a catchphrase for media articles, though more often than not they end in nothing more constructive than a pretentious nostalgic melancholy. At certain point it would be helpful to go beyond the obvious and to ask back the classic counter-questions, “what crisis? whose humanities?” Humanities are very often related with non-productive enterprises, and perhaps more or less characteristically in China, seen as “studies for the rich and aristocrats.” An evaluation of the truism of these impressions to a large extent constitutes the ground of arguments on both sides.

For debate novices or those with relatively light research, pro side will typically make arguments that engages with either individual financial instability of humanities students or the socio-economic unsustainability of technically unproductive cultural departments. They might also mention the vast inequality of cultural capital distribution and touch upon some form of sociological critique that disenchants an almost superstitious public fascination with “knowledge for its own sake” or an unthinking upholding of cultural preservation.

Con side would foreseeably invoke the classic liberal arguments on the importance of culture and even the ancient Greek philosophy on personal enlightenment, which conveniently sugarcoats humanities studies with a perennial and timeless essence which could hardly be fundamentally rejected. More mindful debaters would more specifically situate the value of critical studies within the however-characterized present age (e.g., by vast information overload, AI/technology proliferation, fast food culture, etc.), and be more creative and visionary in their rhetorical construction of a future labour market. It would behoove the more advanced debaters to dive deeper in the history of universities and of humanities, and focus not only on the present value (economic or philosophical) of a certain set of knowledge, but also on the institutional background in which certain knowledge is constructed, circulated, and spread at large. When debaters get to this stage, they shall become discontent with a mechanic definition of “humanities” or a fixed conception of “higher education,” and would naturally consider these terms as phenomenon in transformation.

Merely as an indicative example, pro could track how technology has been changing the patterns of humanities research or the mode of knowledge transmission in the past several decades, and warmly embrace a new decentralized future of humanities that no longer appeals to the authority of academia or depends so much on the medieval apprenticeship pattern of graduate training, while seeing the demise of academic departments in humanities as a natural course of history; similarly, con could also grasp the emergence of explicitly interdisciplinary field of inquiries (e.g., history of science, or certain branch of climate/earth studies) as well as the growing trend of interdisciplinary cooperation in the ever-more specialized academia, and point toward a new future of academic research beyond the mere preservation of the existing crippling institutions. There are surely many more different colorful imaginations of future education and society. For all levels of debaters, this topic should present plenty of intellectual challenge.

05

Education

From the perspective of the topic alone, unlike other niche technological or political topics that debaters would soon toss behind after tournaments, this topic particularly forces debaters to think about the “meta” level of their education and the nature of cultural social reproduction. There is a good chance that this would leave a special resonance even after they are done with the topic. Reflections from debating on this topic might well play a part in their later decisions in picking a major and potentially more.

From the perspective of the debate skills that this topic uniquely mobilizes, this topic requires a strong sensitivity to the strength of evidence and a subtle skill to piece together different narratives. As this is a non-technocratic topic where the ethos of experts is less crucial to evidence credibility, I would hope (however naively) that this resolution would to some extent cool down a rather unhealthy fanaticism in formatted cards (without going through the real research process or knowing the evidence), a dismal debate pathology fostered by the outcome-driven industrial-military complex of debater manufactories.

辩题不是冰冷的设问,而往往是时代的映射。

希望选手们在从容表达观点、追问既有答案、

质疑固定模板的过程中,

逐渐成长为真正“会思考的人”

用理性与智慧

去面对未来的种种可能。