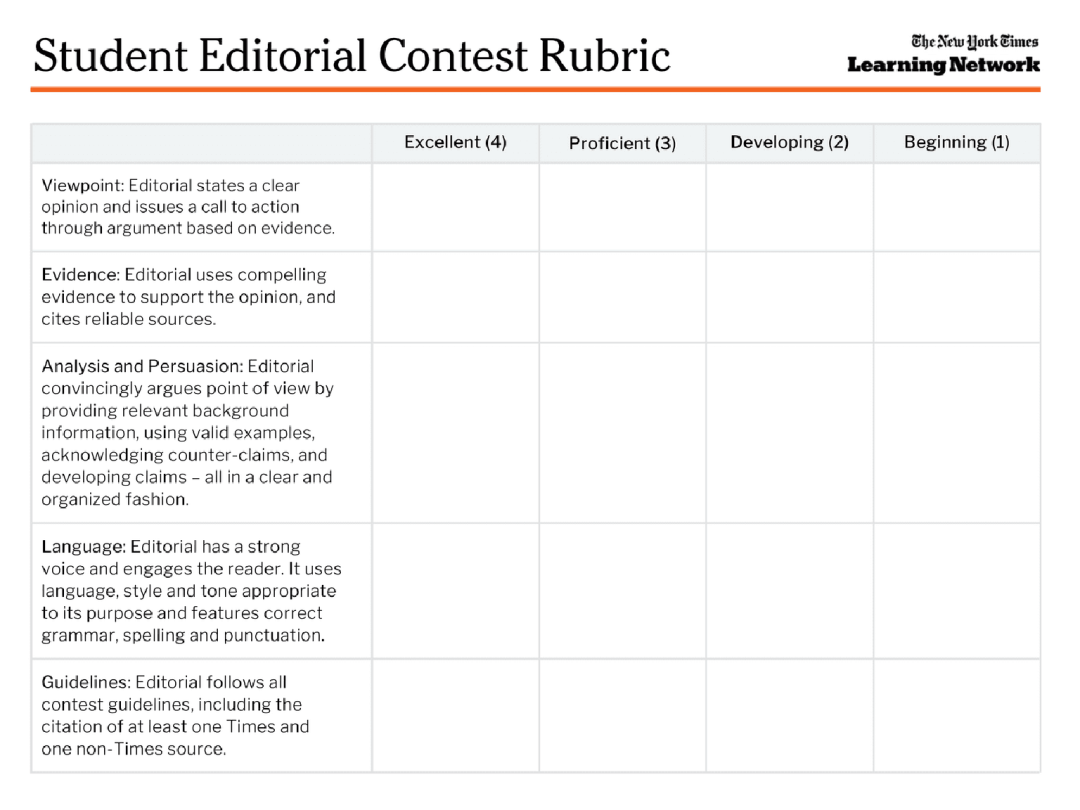

NYT Students Editorial Contest 纽约时报中学生社论竞赛 是纽约时报一系列学生写作竞赛之一,比赛邀请学生将对各类社会话题的想法变成正式的、简短的、以证据为基础的说服性文章,就像纽约时报每天发表的社论一样。

比赛鼓励学生通过使用多种消息来源来拓宽自己的新闻渠道,了解对所选问题提供各种观点的消息来源。第十届纽约时报中学生社论竞赛目前已开启申报提交,如果你积极探索世界,关注社会时事热点,也期望能在竞赛中提升自己的写作能力来了解一下这个能让文理科生“爬藤”的赛事,抓紧时间准备作品吧!

适合对象

全球13-19岁对文学评论写作感兴趣的中学生们均可参加,可个人提交作品,也可以团队名义提交作品(纽约时报工作人员子女不能参加)。

比赛时间

作品提交截止日期:2023年4月12日

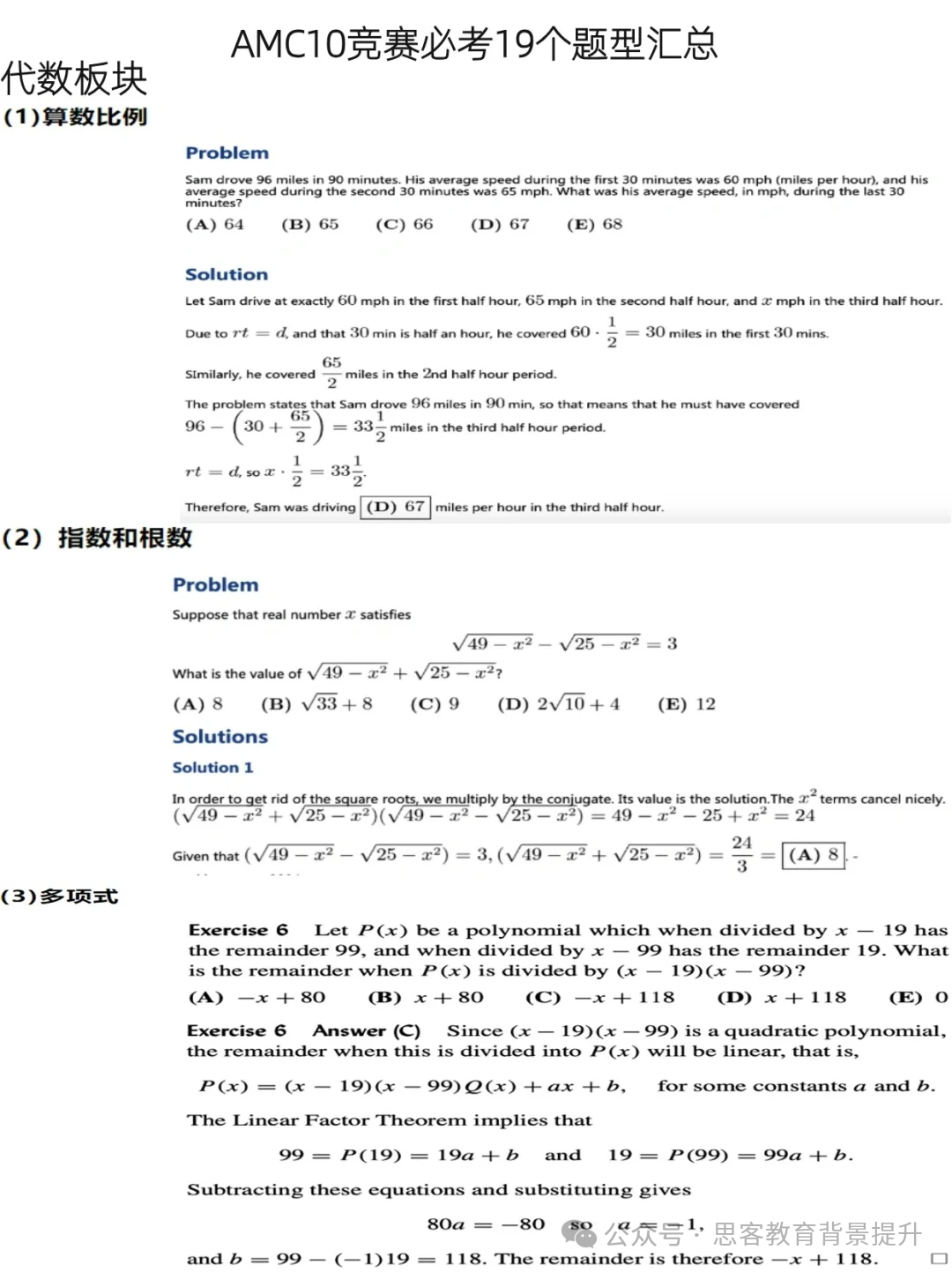

参赛规则

1、选择一个你关心的话题(不管它是不是在纽约时报网站上讨论的话题)然后从《纽约时报》内外的来源收集证据,写一篇简明的社论;

2、所有引用需要注明出处,至少1处来自《纽约时报》过往文章,至少1处来自《纽约时报》所刊文章之外的可靠来源;

3、字数不得超过450词,所以要确保你的论点足够聚焦,并能提出一个强有力的理由。(请注意:标题和参考来源的字数,不计入450字的限制);

4、你可以自己独立一人写社论,也可以和一个小组一起写,但每个学生只提交一篇社论。

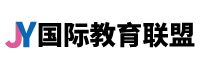

评审标准

奖项设置

Winners

Runnerup

Honorable mention

三类奖项

往届优秀作品

We Cannot Fight Anti-Asian Hate Without Dismantling Asian Stereotypes

We are honoring each of the Top 10 winners of our Student Editorial Contest by publishing their essays. This one is by Madison Xu, age 16.

Women at a memorial outside the Gold Spa in Atlanta, where three Korean women were shot and killed on March 16. Related Opinion EssayCredit...Chang W. Lee/The New York Times

By The Learning Network

Published June 15, 2021Updated Oct. 26, 2021

This essay, by Madison Xu, age 16, from Horace Mann School in the Bronx, N.Y., is one of the Top 10 winners of The Learning Network’s Eighth Annual Student Editorial Contest, for which we received 11,202 entries.

We Cannot Fight Anti-Asian Hate Without Dismantling Asian Stereotypes

A few weeks ago, my aunt decided to close the nail salon she had been running for years. Early on in the pandemic, her business was hit hard, regulars refusing to return and associating her salon with the spread of Covid. Now, she fears for the safety of her salon employees — most of them Asian and Asian-American women.

The New York Times has documented a surge of anti-Asian hate crimes during the coronavirus pandemic, including the deaths of six Asian women during the recent mass shooting in Atlanta. These incidents have rightly sparked protests and outrage, yet there can be no effective response unless we look beyond easy explanations. Talk of the former president’s xenophobic rhetoric, or the shooter’s “sex addiction,” only serves to distract from the underlying issue: America’s history of stereotyping, fetishizing and oppressing Asians and Asian-Americans — especially women.

By the 20th century, mainstream media and popular culture had already categorized Asian women into tropes still resonant today, from the hypersexual “Dragon Lady” to the docile “Lotus Flower.” Predating the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Page Act of 1875 made it unlawful for East Asian women to enter the United States without proof that they were “virtuous.” That Asian women were painted as a “moral contagion” becomes even more chilling when juxtaposed with the Atlanta shooter’s claim that the massage parlors were, “a temptation for him that he wanted to eliminate.” Objects of desire easily become objects of hatred. The key: both are things for the dominant class to fetishize, feel entitled to — or dispose of.

By now, many Americans understand how negative stereotypes of Black and Latinx people in the United States have enabled police brutality, anti-immigrant hysteria and violence. However, we tend to react differently to Asian stereotypes. While there are plenty of derogatory tropes (think bad drivers who eat dogs), Asians in this country are often viewed as smart and industrious — a “model minority.” But the truth is, all stereotypes are ultimately dehumanizing, stripping people of their individuality and objectifying them in ways that can lead to shameful violations like the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

Perhaps most dangerously, stereotypes like the submissive “Oriental” serving girl create artificial roles that women are forced to play, or to be punished for “not knowing their place.” When the dominant class feels threatened, even model minorities suddenly become invading Others, the alien “them” displacing “us” and threatening what is rightfully “ours.”

Until we stop regarding Asian stereotypes and the fetishization of Asian women as innocuous, Asians and Asian-Americans will continue to face the threat of racist violence. Recognizing that anti-Asian prejudice is deeply rooted in American history is the first step toward dismantling those dangerous stereotypes.

Works Cited

Jeong, May. “The Deep American Roots of the Atlanta Shootings.” The New York Times, 19 March 2021.

Lang, Cady and Paulina Cachero. “How a Long History of Intertwined Racism and Misogyny Leaves Asian Women in America Vulnerable to Violence.” Time, 7 April 2021.

为什么要保护新加坡的“丑陋”建筑”?

难道只有全球流行病才制止校园枪击事件?

如何消除对亚裔的刻板印象?

......

这些话题均来自于第八届NYT社论竞赛获奖作品。参赛选手用简明扼要的语言叙述社会现象,论证背后的因果逻辑,选题天马行空,内容却引人深思。

Editorial Contest 是系列比赛中含金量较高的一项,也广受包括中国学生在内的世界各地学生的欢迎。比赛要求学生对社会现象进行评论,包罗万象,往年出现过的题材包括而不限于反亚洲仇恨、气候变化、低薪教师、校园枪击案、黑人人权、暴雪天气、电子游戏文化等,特别能体现学生对于时政的了解程度。

参赛建议

1、竞赛主办方希望参赛者通过搜集各方面资料能够深入思考自己选择的社论主题,尤其是针对同一事件的不同角度和不同看法。同时,也要确认所搜集的信息和资料都是来自于权威媒体;

2、对于所搜集的资料数量,主办方并没有限制。基于以往的经验,衡学君强烈建议参赛的同学们至少援引一篇《纽约时报》里的社论和一篇其他报刊的社论,记得要在文中标注好引用,尽量让读者和评委一目了然你观点所援引的资料来源;

3、无论是直接引用还是间接引用,你都需要非常小心——主办方不希望在搜索引擎里搜到与你文中一模一样的文字。所以,在写作中一定要记得不要抄袭,即使不是你有意为之;

4、如果你是以团队形式完成的,请记得在提交作品时写好所有小组成员的名字,你已经加入了小组,就不能以个人的形式提交该作品。

如果同学们有这些想要表达的想法,就可以参加《纽约时报》的学生社论比赛。以简短的评论文章就大大小小的问题提出了令人信服的论点,以强有力的证据来论证你的想法并说服大家,这就是社论比赛的核心所在。

作为进入知名大学的关键助力项目,竞赛的意义越来越重要。标化内卷到日益趋同的情况下,当大学难以从成绩高低上来筛选,背景就成了重要依据。对于同学们来说很有必要尽早准备类似纽约时报写作竞赛这样的国际竞赛,从而在大学申请时展示自己的社会参与度与学术发展潜力。

参赛收获

1、高含金量和认可度

获奖文章更将会在《纽约时报》网站刊登 ,并且有机会出现在印刷版的《纽约时报》上,可以增加自己的申藤筹码。一旦获奖,纽约时报的知名度、曝光率和全球认可度都会给这份荣誉增添不少分量;

2、申请助力和加成

众所周知,大学的招生录取过程大多采取综合性评估的方式,全方位地考察学生的“硬实力”和“软实力”。此时,一篇思想深刻、用词老道,或是能充分彰显自己的个性的好文章就可能成为一份具有价值的写作样本,让你从众多竞争者中脱颖而出;

3、写作经验和能力的提升

无论任何专业方向,写作能力都会是你未来漫长的学术乃至职业生活中必不可少的核心能力。为了能在大学阶段走得更远更顺,一定要从早期就打下扎实的写作基础,积累丰富的写作经验,在每一次的尝试和练习中不断成长;

4、兴趣话题的探索

即使是写作能力不那么突出的学生,也可以通过这一系列赛事所提供的机会,拓宽自己的知识面、阅读面,或是对自己感兴趣的话题领域展开更深度的探索和思考。