Scholastic Art & Writing Awards美国学术艺术与写作奖,创办于1923年,是全球规模最大、历史最悠久的青年艺术与文学竞赛,旨在发掘7-12年级学生的卓越创造力。

每年吸引逾33万件投稿,由顶尖艺术家、作家及学者评审,颁发地域性与全国性奖项,为获奖者提供展览、出版及奖学金机会,助力升学与职业发展。

适合对象

竞赛面向7–12年级、年满13岁的学生开放,参赛者需为美国或加拿大在校学生,包括就读于美加学校的国际学生。

欢迎所有对艺术创作、文学写作、思想表达感兴趣的学生积极参与,无需专业背景,鼓励多元表达与原创探索。

比赛时间

作品提交:每年9月

截止日期:因地区而异,每年12月

结果公布: 州奖项1月,全国奖项3月,颁奖典礼6月

竞赛类别

竞赛设有28个项目,其中艺术17项,写作11项,涵盖范围广阔:

1、ART(艺术类)包括下面17个项目:

Architecture & Industrial Design 建筑与工业设计

Ceramics & Glass 陶瓷与玻璃

Comic Art 漫画艺术

Design 设计

Digital Art 数字艺术

Drawing & Illustration 绘画与插图

Editorial Cartoon 社论漫画

Expanded Projects 拓展项目

Fashion 时尚

Film & Animation 电影与动画

Jewelry 珠宝

Mixed Media 混合媒体

Painting 绘画

Photography 摄影

Printmaking 版画复制

Sculpture 雕塑

Art Portfolio 艺术作品集(仅限12年级毕业生)

2、WRITING(写作类)包括下面11个项目:

Critical Essay 批判性文章

Dramatic Script 剧本

Flash Fiction 微型小说

Journalism 新闻作品

Humor 滑稽幽默作品

Novel Writing 小说

Personal Essay & Memoir 个人自述与自传

Poetry 诗歌

Science Fiction & Fantasy 科幻小说

Short Story 短篇故事

Writing Portfolio 写作作品集(仅限12年级毕业生)

投稿要求

语言:英文

格式:匿名提交(不得标注姓名/学校),非虚构作品需化名人物。

写作规范:标准字体,禁止插图/超链接,需注明引用来源。

国家级奖项

"全美中学生艺术与写作大赛" 奖项设地方级及国家级两个级别的奖项,同时会给获奖作品提供展览,出版及授予奖学金的机会。

1、Regional Awards 地区奖项

包括金钥匙(Gold Key)、银钥匙(Silver Key)、荣誉提名(Honorable Mention)、美国声音提名(American Voices Nominee)和美国视野提名奖(American Visions Nominee),所有参赛者都有机会获得这些奖项,获奖奖品将在地区庆祝仪式,展览, 以及邮寄方式颁发。

2、National Awards 国家奖项

包括金牌、优异银牌、银牌和奖学金。地区奖项中的”金钥匙“获奖者将自动获得参与国家奖项评选的资格,竞赛官方网站于每年春季公布所有国家奖牌得主的名单。

3、American Voices (美国声音)与 American Visions (美国视野)奖

每项地区级比赛将提名五位参赛者获得美国声音奖或美国视野奖。被提名者必须拥有一部金钥匙获奖作品,其作品须出自作者原创,且作品中的声音或视觉是真实的。每个地区提名过程彼此各异。评审员可能会根据才能表现,不同媒介,观点及背景的体现等多种因素综合考量。国家级评审则会从各个地区的众多提名者中选取一位作为最终美国声音或美国视野的获奖者。

4、National Winners Ceremony 国家奖发奖仪式

竞赛官方每年6月在纽约市的卡内基大厅为数百名学生及其指导教师举行盛大的仪式,仪式中会邀请美国的名流一起见证获奖者的荣耀时刻。最近的仪式中邀请到的特别嘉宾包括奥普拉·温弗瑞(著名主持人)、蒂姆·冈恩(时尚顾问、电视名人)、亚历克·鲍德温(演员,制片人)、索尼娅·曼萨诺(知名女演员)、泰塔斯·伯吉斯(知名男演员)等。

5、Exhibitions 展览

每年的获奖学生作品都会参与到地区展,国家展,及巡回展览的橱窗展示中。

6、Publications 出版物

《最佳青少年艺术》和《最佳青少年写作》每年都刊登精选学生作品,同时竞赛的《年鉴》中会列出所有国家级获奖者名单。

7、Scholarships 奖学金

国家级获奖者有资格获得最高达12500美元的奖学金。

往届获奖作品鉴赏

From Opportunity to Exclusion: The Impact of the Chinese Exclusion Act on Immigrant Communities

By Juntao Ye

Introduction:

The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act marked a turning point in American immigration policy. More than just a piece of legislation, it institutionalized widespread discrimination by limiting immigration, denying citizenship, and restricting employment opportunities for Chinese immigrants between 1882 and 1900. At a time when the American West was celebrated as a land of opportunity, Chinese immigrants instead faced exclusion, hostility, and systemic barriers, further entrenching a long history of marginalization.

In the 19th century, political instability and the lack of economic opportunities in China also drove Chinese workers abroad, with America as one of the most popular destinations. At the time, China was grappling with economic downturns as a result of its defeat in the Opium War. As a result, many Chinese workers immigrated to the United States to pursue economic opportunities. These new Chinese immigrants often faced enormous financial challenges: they often shouldered the burden of sending money back to China to support their families, in addition to repaying the hefty loans to Chinese merchants who had paid for their travel to America.

The influx of Chinese immigrants unsettled the US labor market at the time. Desperate for money, Chinese laborers were willing to work for less pay.1 In addition to financial circumstances, Chinese laborers were forced to settle for lesser wages due to their lack of political power. White American laborers often demanded significantly higher wages and generally had a more robust political standing to bargain for higher wages.2 With the influx of Chinese laborers, however, white laborers felt threatened and thus came to resent the Chinese laborers, who had squeezed them out of their jobs. 3 Anti-Chinese sentiment grew as a result. With the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, this sentiment was codified into law.

Confronted with animosity and hostility from their white counterparts, Chinese workers began to build self-sufficient and close-knit communities that became known as Chinatown. These enclaves provided essential support systems for Chinese immigrants, offering housing, employment, and social networks that helped them navigate the harsh realities of exclusion and discrimination. Chinatowns served as cultural and economic hubs, preserving Chinese traditions, language, and identity while also fostering solidarity among residents. However, the establishment of these communities also reinforced social and cultural isolation, as the legal and societal barriers imposed by the Chinese Exclusion Act effectively confined Chinese immigrants to these segregated spaces. This paper examines the multiple effects of the Chinese Exclusion Act, including legal and social responses. It hopes to provide a detailed investigation of Chinese immigrant life in late 19th-century America.

Legal Exclusion:

The Chinese Exclusion Act, approved by Congress and signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, deprived people of Chinese descent of any rights regarding entry into US territory and denied the majority of employment prospects. The act intended to reduce the number of Chinese immigrants to the United States, notably in California. It strips many Chinese Americans of their citizenship and causes people of Chinese descent to be ineligible for citizenship. According to the U.S. national census in 1880, there were 105,465 Chinese in the United States, compared with 89,863 by 1900 and 61,639 by 1920.4

The Chinese Exclusion Act, however, did not restrict Chinese immigration by a direct quota system; it did so by making the entry to the country difficult and uncertain. Section 2 of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act stipulates that any captain knowingly transporting Chinese laborers to the United States and permitting their disembarkation will be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor. Upon conviction, the captain could face fines of up to $500 per laborer and a maximum imprisonment term of one year.5 The section opposes Chinese immigrants' right to enter the nation by any maritime transportation and considers the act of transferring Chinese immigrants unlawful. The section states,

and every such Chinese laborer so departing from the United States shall be entitled to, and shall receive, free of any charge or cost upon application therefor, from the collector or his deputy, at the time such list is taken, a certificate, signed by the collector or his deputy and attested by his seal of office, in such form as the Secretary of the Treasury shall prescribe, which certificate shall contain a statement of the name, age, occupation, last place of residence, personal description, and facts of identification of the Chinese laborer to whom the certificate is issued, corresponding with the said list and registry in all particulars.6

Section 4 of the Act further entrenched exclusionary mechanisms by requiring Chinese immigrants to provide extensive legal documentation and certificates verifying their personal information. Vessel masters were mandated to compile detailed registries of all Chinese laborers on board, including their names, ages, occupations, physical features, last residences, and other identifying details. These registries had to be securely stored in the local customs house.7 Unlike immigrants from other nationalities, Chinese immigrants were uniquely subjected to this invasive bureaucratic scrutiny, highlighting the targeted and discriminatory nature of the law.

In case any Chinese laborer after having received such certificate shall leave such vessel before her departure he shall deliver his certificate to the master of the vessel, and if such Chinese laborer shall fail to return to such vessel before her departure from port the certificate shall be delivered by the master to the collector of customs for cancellation.8

The mechanisms outlined in Sections 2 and 4 worked together to make immigration nearly impossible for Chinese laborers, effectively barring them from entry. These provisions not only restricted their freedom but also institutionalized their exclusion through legal and administrative measures.

The oppressive nature of these measures extended to Section 12 of the Act, which stated,

That no Chinese person shall be permitted to enter the United States by land without producing to the proper officer of customs the certificate in this act required of Chinese persons seeking to land from a vessel. 9

This section makes it more difficult for Chinese immigrants to enter the country. The Chinese Exclusion Act aimed to maximize decisions and restrictions made by the United States proper officers on Chinese immigrants entering the land from water. The permissions for entry were followed by multiple restrictions and requests from Chinese immigrants to provide legal papers and certificates of residence while entering the United States by maritime transportation. The legitimacy of Chinese immigrants' admission into the US is not decided by this set of formal entry procedures but is ultimately determined by strong US customs authorities on whether or not to admit these Chinese immigrants after arduous processes.

The Chinese Exclusion Act, with its stringent legal restrictions and discriminatory practices, cast a shadow over Chinese immigrants' prospects and rights in the US territory. The act not only systematically targeted Chinese immigrants, curtailed their ability to enter the country, but also laid the groundwork for pervasive social discrimination and hostility, as evidenced by propaganda and exclusionary measures. This legislative framework, coupled with societal prejudice, created formidable barriers to integration and undermined the fundamental principles of equality and inclusion.

Together, Sections 2, 4, and 12 illustrate how the Chinese Exclusion Act layered exclusionary mechanisms to restrict Chinese immigration systematically. By criminalizing transportation, enforcing invasive documentation, and granting broad authority to customs officials, the Act institutionalized the marginalization of Chinese immigrants. These provisions not only barred entry but also created a hostile environment that questioned the legitimacy of Chinese immigrants’ presence in the United States at every step, solidifying their exclusion and underscoring the Act’s discriminatory intent.

Social Exclusion:

Beyond legal barriers, Chinese immigrants faced widespread social discrimination and hostility in California during the late 19th century. The Chinese Exclusion Act legitimized and intensified anti-Chinese sentiment, leading to further discriminatory practices in employment, housing, and social interactions. Chinese immigrants were often subjected to violence, harassment, and exploitation by employers and fellow workers.10 Discrimination against Chinese immigrants not only deprived them of employment opportunities but also created a hostile environment that hindered their integration and mobility within American society.

Chinese immigration had not exceeded 50 individuals annually before 1854. Following gold was discovered in California in 1854, this number increased to 13,100. For the subsequent ten years, it then relatively steadied between 3,000 and 7,000. However, the relative stability does not represent the disappearance of crisis and enmity. The social violence generated from the antipathy toward Chinese immigrants has not only happened in California but throughout the western United States territory (see Fig. 1).11

This anti-Chinese sentiment was manifested in riots. On November 3, 1885, in Tacoma, a 300-man mob drove 700 Chinese out of their homes, forced them into wagons, and boarded the Portland-bound train. Two Chinese died in the process. John Arthur of Tacoma wrote with "genuine delight" to Governor Squire: "Tacoma will be sans Chinese, sans pigtails, sans moon-eye, sans wash-house, sans joss-house, sans everything Mongolian" after the Chinese in, "Tacoma is escorted out of town and put upon freight and passenger trains." 12 Hearing the news of the violence, 150 Chinese fled the neighboring city of Seattle.

Not long after, 350 of the remaining workers were forced out. Although the riots finally ended on November 8, with the help of federal troops sent in by President Grover Cleveland, the trend of violence continued.13

A year later, on February 7, 1886, in Seattle, 350 Chinese were forced out of their homes, and most were shipped to San Francisco.14 In Eastern Washington, 31 Chinese miners were executed in 1887.15 The same year, Tacoma again expelled its Chinese residents. This time, their number was close to three thousand.16

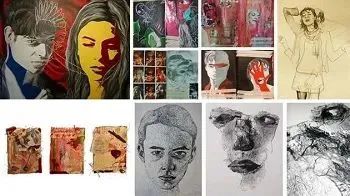

Figure 1: Poster announcing the democratic passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act.17

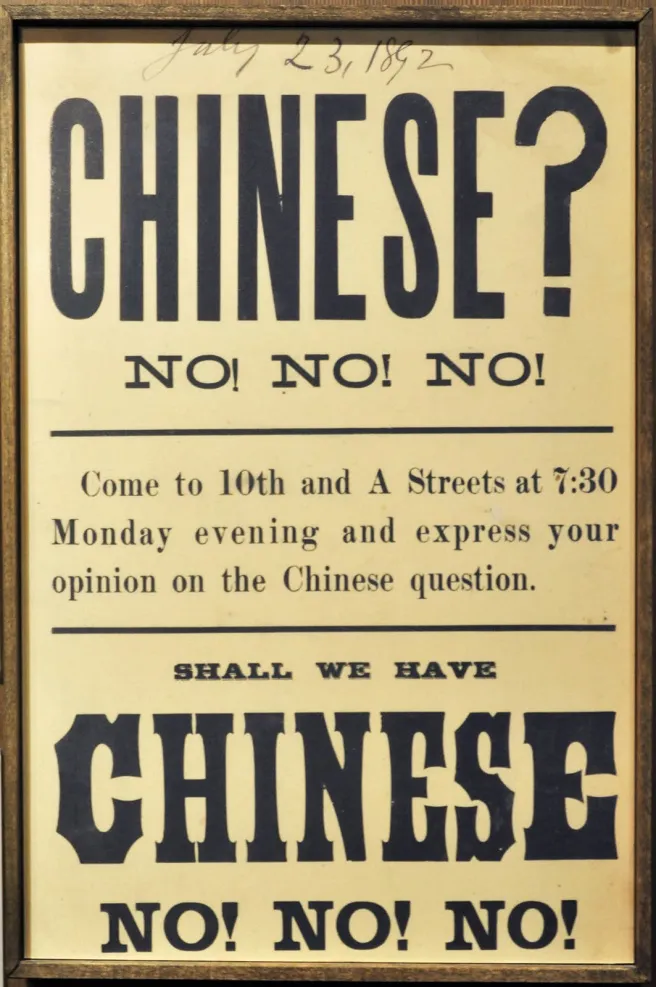

Figure 2: Handbill From Anti-Chinese Rally in Tacoma, Washington, July 23, 1892.18

The riot was both a result and a reflection of the broader antagonism toward Chinese people. Such kinds of violence were perpetuated by racist rhetoric in popular media. For example, the poster announcing the democratic passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, published in 1882 by the order of Democratic County Central Committee provoked the White public to agitate for the passage of the Chinese ExclusionAct: “Come out and ratify! Come, everyone!” “No more Chinese!” emphasizes the deliberative, targeted hostility toward Chinese immigrants. This poster showed that anti-Chinese policies were central to American political discourse at the time and garnered national attention.

Figure 2, the handbill originated from an anti-Chinese rally scheduled for July 23rd, 1892, in Tacoma19 Contains information such as Shall we have Chinese? No! No! No!” Addressing a similar purpose of conducting propaganda of hatred toward Chinese immigrants in local society. In the wake of such propaganda campaigns, Chinese immigrants found themselves isolated and ostracized. The posters often depicted Chinese immigrants as undesirable, untrustworthy, and a threat to the well-being of society by using derogatory language, exaggerated stereotypes, and dehumanizing imagery. These depictions reinforced negative perceptions and stroked fears that Chinese immigrants were a danger to social and economic stability. This inflammatory messaging contributed to widespread fear and resentment, encouraging locals to support exclusionary policies and participate in acts of discrimination and violence against Chinese communities.

The pervasive anti-Chinese sentiment perpetuated by these posters exacerbated the already challenging conditions faced by Chinese immigrants in their daily lives. The atmosphere of hostility fostered by the propaganda posters not only undermined the sense of belonging and community cohesion among Chinese immigrants but also perpetuated a cycle of discrimination and prejudice that further entrenched their marginalized status in society.20

Chinatown: A Double-sided Sword

The establishment and expansion of Chinatowns in 19th-century America reflected both the resilience of Chinese immigrants in creating safe havens and the cultural barriers that deepened their segregation from broader U.S. society. Chinatowns came into existence due to the substantial influx of Chinese immigrants into the cities. By the turn of the 19th century, Chinatowns had sprung up in cities, from San Diego to El Paso to Connecticut, and formed a network that crossed the continent. With the completion of the railroads and the end of the gold rush, Chinese immigrants moved in increasing numbers to urban areas. There, they began to congregate in Chinese-only neighborhoods that functioned as separate, nearly independent, cities within the city.21

The passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act created animosity and hostility between white persons targeting Chinese immigrants22 and, as one of the factors that led to the creation of Chinatowns, Chinese immigrants moved in increasing numbers to urban areas and began to live in Chinese-only neighborhoods with limited interactions with people outside of the community, further resulting in an isolated living environment in a diversified society for Chinese immigrants.23

With limited choices, their place of residence is restricted to Chinatown only. They were forced to work inside the bounds of Chinatowns only. Chinatowns became places of poverty, turmoil, drugs, and crime. White Americans would consider Chinatowns to be isolated islands in the metropolis, reinforcing stereotypes and fueling prejudice that justified their exclusionary attitudes and policies.

The rapid growth of Chinatowns reinforces a sense of separation between the Chinese immigrant population and the broader American society. The majority of Chinese immigrants spent their entire lives in the only friendly zone in the entire US territory—Chinatown. The cultural differences in the cities around the US created a great chasm between the Chinese immigrants and White Americans.

Conclusion:

A pivotal moment in American immigration history, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 represented a sharp break from the principles of opportunity and tolerance. A clear aspect of the Act affected Chinese immigrants in that it made it more difficult for them to integrate economically, socially, and culturally. This had a lasting effect on their communities and influenced American perspectives on immigration and diversity for the decades to come.

The Act's intentional targeting of Chinese immigrants through legislative measures highlights the discriminatory character of immigration laws and their adverse impact on marginalized people. It also underscores the widespread prejudice and hostility that Chinese immigrants encounter. Furthermore, the act’s role in fostering the growth of Chinatowns highlights the difficulty and isolation faced by Chinese immigrants as they strive to realize the American Dream. The Chinese Exclusion Act serves as a sobering reminder of the difficulties minority groups and immigrants encounter in their pursuit of equality and justice, as seen through the prism of history.