题目:What does economics tell us about the benefits and costs of immigration? What policy should we adopt?

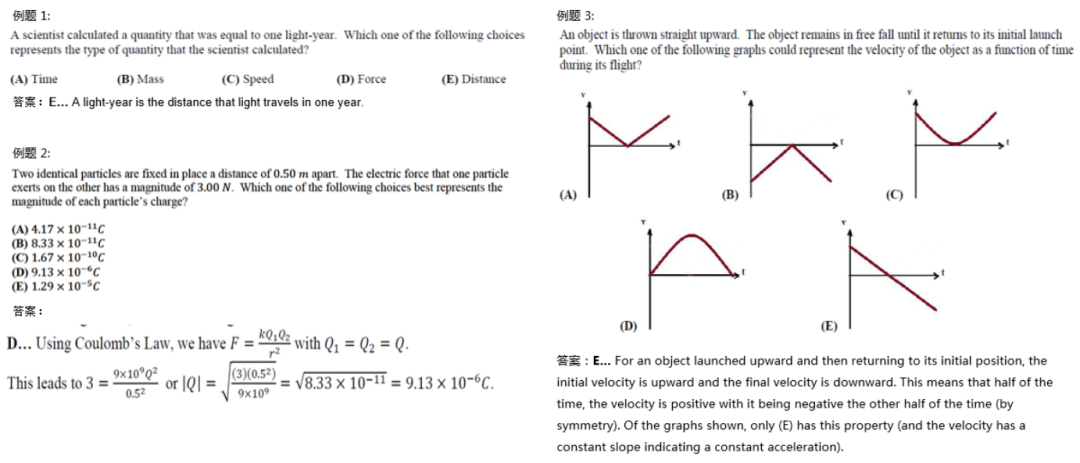

美国总统川普最近表达了许多公民的担忧,他宣称:“非法移民伤害了美国工人;美国纳税人负担;还有……每年耗费我们国家数十亿美元。英国也表达了类似的情绪,当地工人害怕“波兰管道工”,澳大利亚工党领袖比尔·肖顿警告说,工作签证“削弱了当地的就业、工资和工作条件”。乍一看,似乎可以合理地得出这样的结论:由于就业机会的数量固定,移民对本土工人构成了威胁。然而,这种马尔萨斯逻辑错误地假设移民是当地人的完美替代品,并且劳动力需求是静态的。

最近的实证研究表明,公司、工人和市场是动态的,能够适应扩大的劳动力虽然大规模移民可能会影响分配,但几乎没有证据支持这样的说法:从宏观层面上看,移民会压低工资,推高失业率,或加重纳税人的负担事实上,经济理论和实证研究表明,从长远来看,移民提高了生产率、工资和生活水平在全球层面,研究人员估计,消除劳动力流动的所有障碍将使世界GDP翻一番这一排名的惊人增长表明,国际移民政策值得仔细考虑。

移民是一个复杂而情绪化的问题,但对这个问题的任何认真研究都必须以事实为基础。幸运的是,现有的经济学文献提供了实证证据和分析框架,以理性地审视这一问题,首先是当今世界上大约2.6亿[8]移民和另外7.5亿bb0移民背后的推动力,如果有机会,他们将永久迁移到另一个国家。诺贝尔经济学奖得主约翰·希克斯(John Hicks)在其1932年首次发表的开创性著作中提出,“净经济优势的差异,主要是工资的差异,是移民的主要原因。1987年,哈佛大学经济学家George Borjas在Andrew Roy工作的基础上采用了一个选择模型,以证明潜在移民除了考虑相对收入水平外,还考虑技能的相对回归和技能的可转移性

个人会权衡移民的好处和移民带来的成本和障碍。例如,东道国的政策可能针对特定的个人属性或限制移民的总数。合法移民必须支付护照、签证和交通费用。寻求非法入境的无证移徙者可能会付钱给走私者或招致重大人身风险。一旦进入东道国,新移民可能缺乏及时找到合适就业所需的当地网络、证书或劳动力市场专业知识。此外,语言障碍、不熟悉的文化规范和社会孤立也可能带来心理上的代价。

尽管存在这些挑战,但移民带来的潜在生产力收益是巨大的。在完全竞争的劳动力市场中,每个工人的工资都与他创造的价值相称。移民使工人能够通过迁移到生产率更高的地方来寻求更高的工资。这产生了更有效的劳动力分配,经济学家估计,这为全球产出增加了130万亿美元即使世界上5%的最贫困人口迁移到发达国家,世界国内生产总值的增长也将超过完全消除商品、服务和资本流动的所有国际壁垒所带来的增长然而,尽管有潜在的好处,几乎每个发达国家都对移民实行限制

推动这些限制的一个因素是,许多人认为移民压低了当地人的工资然而,在实践中,由于语言、职业和技术技能的差异,大多数移民工人并不是本地工人的紧密替代品,因此,他们不竞争相同的工作事实上,移民往往是生产的补充,而不是替代品。在一篇经常被引用的论文中,经济学家Giovanni Peri和Chad Sparber提出了一个动态过程,当地人通过转换工作来应对移民的涌入,以利用他们的比较优势这种情况在各个教育领域都存在;受教育程度较低的原住民对受教育程度较低的移民增加的反应是从体力密集型工作转向沟通密集型工作,而当高技能的工程师和科学家进入美国时,受过大学教育的原住民进入管理角色

当然,移民带来的好处并非平均分配。哈佛大学(Harvard)经济学家乔治•博尔哈斯(George Borjas)根据教育程度和工作经验将美国工人分为技能单元。Borjas发现,在某些技能细胞中,移民对周收入有统计上显著的负面影响,尤其是在受教育程度较低的群体中在加拿大、德国和挪威的研究也得到了类似的结果尽管技能细胞技术并没有捕捉到那些随着移民而改变技能组合的当地人可能的好处,但它确实提供了经验证据,表明在短期内,受教育程度较低的当地人的周收入会受到拥有类似技能的移民的影响。

然而,从长远来看,总体工资将随着生产率的提高而提高,研究表明移民和生产率提高之间存在正相关关系。高技能移民能吸引资本投资,促进创新,这两者都能提高劳动生产率低技能的移民工人,如园林设计师和托儿服务提供者,鼓励更多高技能的当地人,特别是妇女进入劳动力市场作为投资者或企业家的移民促进了当地的就业,并扩大了可获得的商品和服务的种类由于移民对本国现有的产品、商业规范和法规有一定的了解,他们能够通过降低交易成本和提供更多的产品种类来促进改善国际贸易的福利

除了对劳动力市场的担忧之外,发达国家的许多公民还担心移民会成为本国纳税人的负担然而,这方面的证据也表明,这种担忧可能是没有根据的。对移民对财政影响的估计各不相同,但对相关文献的调查显示了一些明确的模式。首先,移民对财政的影响往往是积极的,而且相对较小例如,经济合作与发展组织(Organization For Economic Cooperation and Development)在2013年采用静态会计方法进行的一项综合研究发现,在被研究的27个成员国中,有20个国家的移民对财政的净贡献在GDP的0 - 0.5%之间总体而言,实证研究表明,高技能移民较多的国家的净财政正面影响更大,而人道主义移民大量流入的国家的净财政影响更低,甚至是负面影响年轻的移民往往会产生更积极的财政影响,因为他们比年长的移民更健康,参与劳动力的时间更长,更成功地融入社会

移民的好处也延伸到了移民输出国。根据世界银行的数据,最直接的收益来自汇款,通常超过对外援助总额,在9个国家,汇款占GDP的20%以上此外,尽管著名经济学家贾格迪什·巴格瓦蒂(Jagdish Bhagwati)和滨田光一(Koichi Hamada)等人的早期研究警告了高技能移民来源国流失的可怕后果,即所谓的人才流失,但数据显示,如果移民率不超过35%,这些担忧在很大程度上是没有根据的人才流失没有成为现实,因为除了现金支付和投资外,高技术移民还将专业知识和机构改革返还给输出国此外,仅仅是移民的前景就会刺激人口去接受更高水平的教育和培训,其中只有一小部分人最终会离开所有这些因素都提高了输出国的全要素生产和生活水平

尽管对移民来源国和接受国都有好处,但构建公平有效的移民政策是一个复杂的规范过程,必须考虑到历史、政治和社会因素。因此,目前全球各地的移民政策差异很大,从美国的以家庭为基础的政策,到澳大利亚的积分体系,再到阿联酋的客工计划。以家庭为基础的移民往往在入职时收入较低,但工资增长较快,因为他们有更好的社交网络,并有更大的动机来获取当地价值的人力资本基于积分的移民系统偏爱具有特定特征的移民,如教育、职业或语言技能。这些制度导致更多的高技能移民,但这些技能往往不能很好地转移到东道国,而且标准可能不够灵活,无法跟上不断变化的商业环境的动态需求。客工计划为解决劳动力短缺问题提供了更大的灵活性,并可能阻止非法移民,但工人通常在一段时间后返回家乡,并有有限的机会获得社会服务

每一项政策都有相对优势,每一种情况都是独特的,但东道国可以采取一些行之有效的措施来提高移民成功的几率,首先是语言培训。语言技能是至关重要的,以移民为重点的语言项目会带来更大的经济成功和社会融合积极的劳动力市场项目,如求职协助和咨询、工作场所介绍和持续的指导,提高了移民的就业率最后,移民往往在劳动力市场灵活和反歧视法有效的国家取得更大的成功

合理的政策还必须考虑到移民对本土工人的负面影响,尤其是老年人和受教育程度较低的人这是一个特别脆弱的群体,许多政府运营的旨在对这一群体进行再培训和再就业的项目都是无效的然而,利用私营部门力量的项目往往更成功。例如,瑞典工业和工会联合成立了就业保障委员会,德国联邦就业局提供代金券,以支付私人经营的再培训和就业安置服务的费用这些项目更有效,因为它们能更好地识别最需要的技能,并能更快地适应经济环境的变化

尽管经济模型预测,不受限制的国际劳动力流动将带来巨大收益,但在短期内这在政治上并不可行。这样一种渐进的方式,在很大程度上是不可逆转的,更务实的努力。尽管如此,有一个令人信服的理由支持由市场力量而非官僚规则驱动的移民政策。这种方法的一个例子是由诺贝尔奖得主加里·贝克尔(Gary Becker)首先提出的,他呼吁在公开市场上以供需规律决定的价格每天出售一定数量的签证经济学家本杰明·鲍威尔(Benjamin Powell)提出,每年每1000名东道国人口出售5个永久居留权移民签证签证费用可以由移民工人、雇主或第三方(如慈善基金会)支付。支付可以通过传统的贷款,甚至收入分享协议来融资

以市场为基础的方法可能在政治上更可行,因为它吸引了更有生产力和创业潜力的移民,而签证支付有助于政府收入可以说,它比现有的政策更公平,因为进入这个国家不是由家庭关系、原籍国、僵化的积分体系或其他拜占庭式的监管决定的。以市场为基础的政策可以在成功完成一项重大特赦计划后,通过一项程序,允许目前的无证劳工在公开市场上购买签证。在某些情况下,在公开市场上出售永久和季节性两种签证,或向遭受政治或宗教迫害的难民提供相对少量的免费签证,可能会更好地满足一个国家的需要。然而,无论细节如何,自由市场依赖于法治,因此成功的市场化政策——有些人可能会遗憾地说——包括对非法移民及其雇主造成可信且足够严厉的后果。

过去几十年的大量实证分析对移民总体上破坏了当地劳动力市场或给政府预算带来压力的观点提出了质疑。相反,数据表明,从长远来看,移民不仅提高了移民的生活水平,也提高了当地人的生活水平。进一步减少国际劳动力流动的障碍可能会为全球GDP增加数万亿美元尽管移民问题往往是一个情绪化和政治争议性的问题,但潜在移民和未来几代人应该得到基于合理原则和经验证据的深思熟虑的政策,而不是下意识的反应和政治迎合。

Footnotes

1 Donald Trump, “Remarks by President Trump on the Illegal Immigration Crisis and Border Security,” The White House, Roosevelt Room, Washington DC, November 1, 2018, https://www.whitehouse.gov/.

2 Daniel Pimlott, “Migration: Why we need Polish plumbers,” Financial Times, February 22, 2006, https://www.ft.com/.

3 William Richard Shorten, “Protecting Local Workers – Restoring Fairness to Australia's Skilled Visa System,” Bill’s Media Releases, April 23, 2019, https://www.billshorten.com.au/.

4 Giovanni Peri, “Do Immigrant Workers Depress the Wages of Native Workers?” IZA World of Labor, (May 2014), 2.

5 Benjamin Powell, The Economics of Immigration: Market-Based Approaches, Social Science, and Public Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 11-70.

6 Giovanni Peri, “Do Immigrant Workers Depress the Wages of Native Workers?” IZA World of Labor, (May 2014), 1.

7 Michael A. Clemens, “Economics and emigration: Trillion-dollar bills on the sidewalk?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 22, no. 3 (2011), Table 1.

8 United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, International Migration Report 2017: Highlights, (New York, 2017) Table 1, https://www.un.org.

9 Neli Esipova, Anita Pugliese, and Julie Ray, “More Than 750 Million Worldwide Would Migrate If They Could,” Gallop, (December 10, 2018), https://news.gallup.com/

10 John R. Hicks, The Theory of Wages, 2nd ed. (London: Macmillan, 1963), 76.

11 George J. Borjas, “Self-selection and the Earnings of Immigrants,” American Economic Review 77, no. 4 (1987): 551-52.

12 Michael A. Clemens, “Economics and emigration: Trillion-dollar bills on the sidewalk?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 22, no. 3 (2011), Table 1.

13 Benjamin Powell, The Economics of Immigration: Market-Based Approaches, Social Science, and Public Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 2.

14 Ibid., 11.

15 Giovanni Peri, “Do Immigrant Workers Depress the Wages of Native Workers?” IZA World of Labor, (May 2014), 2.

16 Ibid., 8.

17 Giovanni Peri and Chad Sparber. “Task Specialization, Immigration and Wages.” American Economic Journal 1, no. 3 (2009): 135-69.

18 Gianmarco I. P. Ottaviano and Giovanni Peri, “Rethinking the Effect of Immigration on Wages.” Journal of the European Economic Association 10, no. (2012): 191.

19 George J. Borjas, “The Labor Demand Curve is Downward Sloping: Reexamining the Impact of Immigration on the Labor Market,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 118, no. 4 (2003): 1346-48.

20 Cynthia Bansak, Nicole B. Simpson, and Madeline Zavodny, The Economics of Immigration, (London and New York: Routledge, 2015), 183.

21 Cynthia Bansak, Nicole B. Simpson, and Madeline Zavodny, The Economics of Immigration, (London and New York: Routledge, 2015), 188-204.

22 Patricia Cortes and Jose Tessada, “Low-Skilled Immigration and the Labor Supply of Highly Skilled Women,” American Economic Journal Applied Economics 3, no. 3 (July 2011): 110-11.

23 Jennifer Hunt, “Which Immigrants Are Most Innovative and Entrepreneurial? Distinctions by Entry Visa,” Journal of Labor Economics 29, no. 3 (2011): 419-22.

24 Cynthia Bansak, Nicole B. Simpson, and Madeline Zavodny, The Economics of Immigration, (London and New York: Routledge, 2015), 201-02.

25 Chen Bo and David S. Jacks, “Trade, Variety, and Immigration,” Economics Letters 117, no. 1 (March 2012): 243-46, doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2012.04.007.

26 Giovanni Peri, “Do Immigrant Workers Depress the Wages of Native Workers?” IZA World of Labor, (May 2014), 2.

27 Cynthia Bansak, Nicole B. Simpson, and Madeline Zavodny, The Economics of Immigration, (London and New York: Routledge, 2015), 232.

28 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, International Migration Outlook 2013 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2013), doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2013-en.

29 Cynthia Bansak, Nicole B. Simpson, and Madeline Zavodny, The Economics of Immigration, (London and New York: Routledge, 2015), 230-32.

30 Ibid., 230-34.

31 World Bank, Global Economic Prospects 2006 : Economic Implications of Remittances and Migration, (Washington DC: World Bank, 2006), 85-127.

32 Frederic Docquiera and Hillel Rapoport, “Quantifying the Impact of Highly-Skilled Emigration on Developing Countries,” Centre for Economic Policy Research (May 16, 2009): 77.

33 World Bank, Global Economic Prospects 2006 : Economic Implications of Remittances and Migration, (Washington DC: World Bank, 2006), 25-72.

34 Michael Beine, Frederic Docquier, and Hillel Rapoport, "Brain drain and human capital formation in developing countries: winners and losers," Economic Journal 118, no. 4 (2008): Table 1.

35 Benjamin Powell, The Economics of Immigration: Market-Based Approaches, Social Science, and Public Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 23-31.

36 Cynthia Bansak, Nicole B. Simpson, and Madeline Zavodny, The Economics of Immigration, (London and New York: Routledge, 2015), 281-324.

37 Ibid., 313-318.

38 Barry Chiswick and Paul Miller, Handbook of the Economics of International Migration, Volume 1A: The Immigrants (Oxford: Elsevier, 2015), 213-70.

39 Ulf Rinne, “The Evaluation of Immigration Policies,” IZA Discussion Paper 6369 (February 2012): 19-20.

40 Cynthia Bansak, Nicole B. Simpson, and Madeline Zavodny, The Economics of Immigration, (London and New York: Routledge, 2015), 167, 325.

41 Ronald D'Amico and Peter Z. Schochet, The Evaluation of the Trade Adjustment Assistance Program: A Synthesis of Major Findings, Prepared for U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration. (Oakland, CA: Social Policy Research Associates and Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research, December 2012) iv..https://www.mathematica-mpr.com/.

42 Jeffrey Selingo, “The False Promises of Worker Retraining,” The Atlantic, January 8, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/.

43 Thomas K. Grose, “The Worker Retraining Challenge,” U.S. News and World Report, February 6, 2018, https://www.usnews.com/.

44 Julia Lang and Thomas Kruppe, “Labour Market Effects of Retraining for the Unemployed - the Role of Occupations,” German Economic Association Conference Paper, (August 2014): 26. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/100420.

45 Council of Economic Advisers. Addressing America’s Reskilling Challenge. (July 2018): 22. https://www.whitehouse.gov/.

46 Benjamin Powell, The Economics of Immigration: Market-Based Approaches, Social Science, and Public Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 146-54.

47 Benjamin Powell, The Economics of Immigration: Market-Based Approaches, Social Science, and Public Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 147.

48 Ibid.,152

49 Robert W. Fairlie, Kauffman Index of Entrepreneurial Activity, 1996-2011 (Kansas City, MO: Kauffman Foundation, 2013), 10-13.

50 Samuel Bufford, “International Rule of Law and the Market Economy - An Outline,” Southwest Journal of Law and Trade in the Americas 12, (2006): 311.

51 Michael A. Clemens, “Economics and emigration: Trillion-dollar bills on the sidewalk?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 22, no. 3 (2011), 87.

Author’s Note

Unless specified otherwise, this paper will use the word “immigrants” to denote individuals who are not born a citizen of the country where they currently reside. This includes voluntary and humanitarian immigrants, who enter the host country with or without proper documentation, and stay on a temporary or permanent basis.

Bibliography

Bansak, Cynthia, Nicole B. Simpson, and Madeline Zavodny. The Economics of Immigration. London and New York: Routledge, 2015.

Beine, Michel, Docquier, Frederic, and Hillel Rapoport. "Brain drain and human capital formation in developing countries: winners and losers." Economic Journal 118, no. 4 (2008): 631-52.

Bhagwati, Jagdish. “Incentives and Disincentives: International Migration.” Review of World Economics 120, no. 4 (1984): 678–701.

Bhagwati, Jagdish and Koichi Hamada. “The Brain Drain, International Integration of Markets for Professionals and Unemployment: A Theoretical Analysis.” Journal of Development Economics 1, no. 1 (1974): 19-42.

Bo, Chen and David S. Jacks. “Trade, Variety, and Immigration.” Economics Letters 117, no. 1 (March 2012): 243-46. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2012.04.007.

Borjas, George J. “Assimilation, Changes in Cohort Quality, and the Earnings of Immigrants.” Journal of Labor Economics 3, no.4 (1985): 463-89.

-----. Immigration Economics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014.

-----. “Self-selection and the Earnings of Immigrants.” American Economic Review 77, no. 4 (1987): 531-53.

-----. “The Labor Demand Curve is Downward Sloping: Reexamining the Impact of Immigration on the Labor Market.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 118, no. 4 (2003): 1335-74.

Bufford, Samuel. “International Rule of Law and the Market Economy - An Outline.” Southwest Journal of Law and Trade in the Americas 12, (2006): 303-12.

Chiswick, Barry and Paul Miller. Handbook of the Economics of International Migration, Volume 1A: The Immigrants. Oxford: Elsevier, 2015.

Clark, Ximena, Timothy J. Hatton, and Jeffrey G. Williamson. "Explaining U.S. immigration, 1971-98." World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3252, (March 2004): 1-35.

Clemens, Michael A. “Economics and emigration: Trillion-dollar bills on the sidewalk?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 22, no. 3 (2011): 83-106.

Cortes, Patricia and Jose Tessada. “Low-Skilled Immigration and the Labor Supply of Highly Skilled Women.” American Economic Journal Applied Economics 3, no. 3 (July 2011): 88-123.

Council of Economic Advisers. Addressing America’s Reskilling Challenge. July 2018. https://www.whitehouse.gov/.

D'Amico, Ronald and Peter Z. Schochet. The Evaluation of the Trade Adjustment Assistance Program: A Synthesis of Major Findings. Prepared for U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration. Oakland, CA: Social Policy Research Associates and Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research, December 2012. https://www.mathematica-mpr.com/.

Docquiera, Frederic and Hillel Rapoport. “Quantifying the Impact of Highly-Skilled Emigration on Developing Countries.” Centre for Economic Policy Research. (May 16, 2009): 1-114.

Duleep, Harriet Orcutt and Mark C. Regets. "Admission Criteria and Immigrant Earning Profiles." International Migration Review 30, no.2 (1996): 571-90.

-----. "The Elusive Concept of Immigrant Quality: Evidence from 1970-1990." College of William and Mary Department of Economics Working Paper 138 , (March 2013): 1-36.

Esipova, Neli, Anita Pugliese, and Julie Ray. “More Than 750 Million Worldwide Would Migrate If They Could.” Gallop, December 10, 2018. https://news.gallup.com/.

Fairlie, Robert W. Kauffman Index of Entrepreneurial Activity, 1996-2011 . Kansas City, MO: Kauffman Foundation, 2013.

Friedman, Milton. Interview by Peter Brimelow. “Milton Friedman Soothsayer.” Hoover Digest, no. 2, 1998.

Giulietti, Corrado and Wahba, Jackline. “Welfare Migration.” IZA Discussion Paper 6450 , (March 2012): 1-18.

Grose, Thomas K. “The Worker Retraining Challenge.” U.S. News and World Report. February 6, 2018. https://www.usnews.com/.

Hatton, Timothy and Andrew Leigh. “Immigrants Assimilate as Communities, not as Individuals.” Journal of Population Economics 24, no. 2 (2011): 389-419.

Hicks, John R. The Theory of Wages. 2nd ed. London: Macmillan, 1963.

Hunt, Jennifer. “Which Immigrants Are Most Innovative and Entrepreneurial? Distinctions by Entry Visa.” Journal of Labor Economics 29, no. 3 (2011): 417-457.

Jones, Charles I. and Paul M. Romer. "The New Kaldor Facts: Ideas, Institutions, Population, and Human Capital." NBER Working Paper 15094, (June 2009): 1-30.

Lang, Julia and Thomas Kruppe. “Labour Market Effects of Retraining for the Unemployed - the Role of Occupations.” German Economic Association Conference Paper, (August 2014): 1-45. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/100420.

Massey, Douglas S., Joaquin Arango, Graeme Hugo, Ali Kouaouci, Adela Pellegrino, and J. Edward Taylor. "Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal." Population and Development Review 19, no. 3 (1993): 431-66.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. International Migration Outlook 2013. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2013. doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2013-en.

Ottaviano, Gianmarco I. P. and Giovanni Peri. “Rethinking the Effect of Immigration on Wages.” Journal of the European Economic Association 10, no. (2012): 152-97.

Ottaviano, Gianmarco I. P., Giovanni Peri, and Greg C. Wright. “Immigration, Offshoring, and American Jobs.” American Economic Review 103, no. 5 (2013): 1925-59.

Peri, Giovanni. “Do Immigrant Workers Depress the Wages of Native Workers?” IZA World of Labor, (May 2014): 1-10.

-----. “The Effect of Immigration on Productivity: Evidence from U.S. States” Review of Economics and Statistics 94, no. 1 (2012): 348-58.

Peri, Giovanni and Chad Sparber. “Task Specialization, Immigration and Wages.” American Economic Journal 1, no. 3 (2009): 135-69.

Peri, Giovanni, Kevin Y. Shih, and Chad Sparber. “Foreign STEM Workers and Native Wages and Employment in U.S. Cities.” NBER Working Paper No. 20093, (May 2014): 1-44.

Pimlott, Daniel. “Migration: Why we need Polish plumbers.” Financial Times, February 22, 2006, https://www.ft.com/.

Powell, Benjamin. The Economics of Immigration: Market-Based Approaches, Social Science, and Public Policy . New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Rinne, Ulf. “The Evaluation of Immigration Policies.” IZA Discussion Paper 6369. (February 2012): 1-27.

Selingo, Jeffrey. “The False Promises of Worker Retraining.” The Atlantic. January 8, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/.

Shorten, William Richard. “Protecting Local Workers – Restoring Fairness to Australia's Skilled Visa System.” Bill’s Media Releases. April 23, 2019. https://www.billshorten.com.au/ .

Sjaastad, Larry A. "The Costs and Returns of Human Migration." Journal of Political Economy 70, no. 5 (1962): 80-93.

Trump, Donald. “Remarks by President Trump on the Illegal Immigration Crisis and Border Security.” The White House. Roosevelt Room, Washington DC, November 1, 2018. https://www.whitehouse.gov/.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. International Migration Report 2017: Highlights. New York, 2017. https://www.un.org.

World Bank. Global Economic Prospects 2006 : Economic Implications of Remittances and Migration. Washington DC: World Bank, 2006.

Zipf, George Kingsley. "The P1 P2/D Hypothesis: On the Intercity Movement of Persons." American Sociological Review 11, no. 6 (1946): 677-86.